“Even the seemingly most mundane of things—grammar, syntax, sentence structure—even these

were animated by something unseen, dare I say, magical,

behind and beyond them…and each could be a building block,

a concrete gesture, for good or for ill, toward

an imagined future world.” --David Naimon

were animated by something unseen, dare I say, magical,

behind and beyond them…and each could be a building block,

a concrete gesture, for good or for ill, toward

an imagined future world.” --David Naimon

|

If we use the symbol of the family tree, the branches reach ever outward over time. The closer we are to the trunk, the broader and more stable the support. Creative lineage is similar to one’s family lines—by tracing backward through those whose work has influenced and shaped our own, we can begin to see ourselves in the perspective of history. Losing a family member—especially a parent or grandparent—can make the family tree feel unstable, as if we have lost the trunk or the roots, the parts that hold us strong and keep us grounded as we and our own offspring sway high above in the branches.

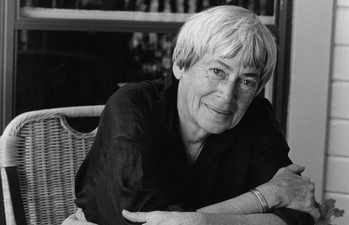

Losing a mentor, a literary hero, can be likewise destabilizing and frightening; it can leave us without one of our intellectual guides. We become acutely aware of all we haven’t had time to ask or learn, and we may want to wring meaning and depth from even the most casual utterance or scrap of writing left behind by a teacher. Luckily for us, then, Conversations on Writing—one of Ursula K. Le Guin’s final projects, a collection of three interviews with Between the Sheets podcast host David Naimon, is all we could hope for in last words. Succinct yet detailed, she addresses both the hows and the whys of her craft. In so doing, she provides a laconic overview of the values that sing through her body of work, underscoring the powerful mind that drove the ideas within the stories. Herein lies the magic of this small volume: Le Guin talks about using imagination, fiction, and poetry because she dislikes making pronouncements about how things should be (her now-legendary National Book Award speech notwithstanding). “I’m grateful to the interviewer who…doesn’t require me to act the Oracle of Delphi,” she says. Yet just as Le Guin makes it clear that she prefers to learn through narrative over theory, her explicit discussion of craft becomes itself a parable for how to live. As she explains: “A function of…real myth as told seriously by serious grownups to others is telling us who we are.” In this way, Le Guin suggests, the words we read and write are creating and recreating the world; they are themselves an important form of action. The book is divided into three separate conversations with Naimon, each introduced via a short essay by him on fiction, poetry, and nonfiction. These are, ultimately, his interviews, and Naimon frames each chapter with anecdotes that remind us that these conversations are personal, in part a result of the questions he thought to ask. If he sometimes works too hard to prove to us his intimacy with this great person, he can be forgiven the impulse. To his credit, he gives her the majority of the space on the page. The interview format invites the reader into their personal space and acquaints us with Le Guin’s spoken voice, not altogether different from the language of her published work, but also more immediate and unpolished. The conversations demonstrate her groundedness, her quick wit, and a pragmatism that borders on stern. She is also telling us that it is in imagination that we find our way—forward, backward, and homeward. Le Guin was notoriously opposed to the policing of genre boundaries, and even though it is clear that she approached her poetry and prose with different attitudes and muses, a number of themes reappear through all three conversations. One has to do with the benefit of understanding structure. At the sentence level, she recalls learning how to diagram sentences from her mother. “For anyone who has that kind of mind, it’s illuminating,” she says. “It’s kind of like drawing the skeleton of a horse. You go: ‘oh, that’s how they hang together!’”

She and Naimon then develop the idea of sentences having bones and structures much in the manner of animals, each form producing its own particular gait. This sensitivity to gait—to rhythm in language—is at the heart of much of Le Guin’s work, both poetry and prose. “Beneath memory and experience, beneath imagination and invention, beneath words, there are rhythms to which memory and imagination and words all move; the writer’s job is to go down deep enough to feel that rhythm and let it move memory and imagination to find the words.” |

Le Guin also addresses structure from the perspective of form: it empowers creation within boundaries, as with certain poetical formulae, like haiku or villanelle—“whether you originated [a certain form] or it’s something you inherited from other artists, you have complete freedom there…It’s a different kind of freedom.” For her, this seems to operate within structural disciplines, too, as with science and poetry: “Science explicates, poetry implicates. Both celebrate what they describe. We need the languages of both science and poetry to save us from merely stockpiling endless information that fails to inform our ignorance or our irresponsibility.” Again, though the approaches are different, both may struggle to untangle, delineate, or provide a holistic experience of the same questions, and yet it is the structure and variety unique to each that lends it insight and meaning.

Another theme is that of imagination. Le Guin comes across as a well rooted and steady thinker, so there is a delight in seeing her commitment to the imaginary. She presents it as something deeply practical, as if fantasy were the most no-nonsense of endeavors. Indeed, she suggests that it is fundamental if we are to survive, that it is through the imagination of myth that we come to know who we are and where we belong. “Home, imagined, comes to be,” she says in her talk, “Operating Instructions.” “It is real, realer than any place, but you can’t get to it unless your people show you how to imagine it—whoever your people are.”

Many of the other themes that surface in this book are common to her work. Gender is mentioned from a number of different angles—women being erased from history and the canon, the usefulness of (and historical arguments for) gender neutral pronouns, and the need to counter the myth of the natural world being connected only to the feminine aspect, thereby relinking all of humanity to the rest of the living realms. The natural world itself, including our relationship to animals, figures prominently. Often Le Guin’s points are illustrated not through her own work, but through beautifully rendered inset pages highlighting examples from other writers. Virginia Woolf, Gabriela Mistral, JRR Tolkien, and George Orwell figure as the grandparents in this creative family tree. There is something disarming about seeing the work that inspired and shaped a Grand Master of science fiction. It pulls her from the firmament and renders her human, curled on a couch with a favorite book and a pencil in hand, much like her own readers who pore over her language for keys to its secret effect. Ultimately Le Guin is telling us that everything we need to know is right there in the language, that there is a magic to that sharing and knowing that is both fundamental and worth protecting, cultivating, examining. She tells us, too, that language creates—as with the people of Anarres, the anarchist society from her book, The Dispossessed: “They realized you couldn’t have a new society and an old language.” She is also telling us that it is in imagination that we find our way—forward, backward, and homeward. “A very large part of knowing who we are is knowing where we came from, where we live now, and if there is a further home to go to, what might it be? Placing yourself among your people within a certain context on the Earth. And it seems to take a lively effort of the imagination to accomplish this.” If this book has a weakness, it is simply that it is too short, a last wink, rife with the wisdom we crave but too brief. Like replaying a last conversation with a loved one, it is easy to want to read too much into these lines as if she had carefully imbued each with every drop of wisdom and intention she could muster—the very opposite of her wishes, perhaps, dreading as she did her turn as Oracle. What she does leave us with, though, is a consistency of purpose and a warmth of spirit, and an enduring call to imagine our ways to a better future. |

REVIEWED BY LARA MESSERSMITH-GLAVIN

Lara Messersmith-Glavin is a writer, editor, and teacher based in Portland, Oregon. Her nonfiction work focuses on women, nature, science, language, and mythology--including her forthcoming memoir on growing up in the Alaskan fishing industry, SPIRIT THINGS. She also serves on the board of the Institute for Anarchist Studies and edits their house journal, Perspectives on Anarchist Theory.When she's not at a desk or in the classroom, she can be found performing onstage with other Fisherpoets, exploring the woods with her child, or swinging kettlebells at the gym where she coaches. Check out her work at queenofpirates.net.

Lara Messersmith-Glavin is a writer, editor, and teacher based in Portland, Oregon. Her nonfiction work focuses on women, nature, science, language, and mythology--including her forthcoming memoir on growing up in the Alaskan fishing industry, SPIRIT THINGS. She also serves on the board of the Institute for Anarchist Studies and edits their house journal, Perspectives on Anarchist Theory.When she's not at a desk or in the classroom, she can be found performing onstage with other Fisherpoets, exploring the woods with her child, or swinging kettlebells at the gym where she coaches. Check out her work at queenofpirates.net.