Playing Hard to Get:

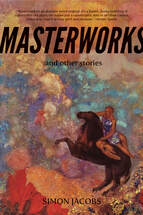

Masterworks and other stories by Simon Jacobs

I am your book reviewer and it is my duty to inform you that I do not comprehend all that I’m asked to read and remark upon.

And you, too, dedicated reader, will almost certainly furrow your brow on occasion, even as you continue turning page after page. Because we can’t furrow anything but our brows, and because some books are Scorpios. If you care about Scorpios, and if you care about “untested, scrappy experimental fiction,” it is worth assessing your orientation to this fact of life and literature. It is, in fact, worth pausing to take this Cosmo-style quiz: Are you the kind of reader that will like, even love, a book, despite having to chase after it? a) Never. I don’t like playing games. Don’t @ me. b) Maybe. I love a challenge, but I might run up against my own ego in the process. c) Sure! I’m so tired of the predictable and basic. I train for obstacle course races every weekend and listen to John Cage on my morning commute. My result: b. I like but do not (yet) understand my relationship with Masterworks and other stories by Simon Jacobs, published by Instar Books. As anyone who has ever dated a sexy but elusive type knows, this is treacherous territory. It begins with a little online stalking. Doing so, I learned that the titular work, “Masterworks,” included within this collection as a 50+ page story, was originally published as a serial in Paper Darts, a “home for art and lit to meet and clash and mix.” There, the story was issued as flash fictions that had characters Priam and Nell perform reenactments of major works of art. In the book, they are collected together, alternating reenactments in an enjoined narrative. This is better than it sounds; it is funny even. It is also perhaps Jacobs’s most straightforward piece in the collection: two characters whose relationship is revealed through imaginative role-play. It’s an inventive work of ekphrasis. But I would rather focus on the more difficult stories that make up the remaining 75 percent of Masterworks. Because I’m 100 percent that bitch?

On our first date, Masterworks took me to an Olive Garden, which I knew about in advance, thanks to the title of the collection’s first story: “Let Me Take You to Olive Garden.” Reader, I was delighted and discomposed. There are three parts to this 10-page story, in three separate Dayton-area restaurants—only one has unlimited breadsticks—with three separate sets of characters who face each other in booths. Details differ in each universe, but everyone drinks Diet Coke and everyone’s universe collapses into a terrifying abyss before the check arrives. The unnamed first-person narrator and their date, Reese, at the Olive Garden, are the first to succumb to the torn fabric of space-time:

“…I decide that Reese is a half-breadstick girl at most, and bizarrely, it still seems to be my turn to ask a question. That said, my capacity is honestly endless; between us, I picture a giant grid, like a mega-calendar, the building blocks of our Great Love, and each blank box comprises a question…But before she can confirm or deny, the ground breaks open to the right of our table, and in the next second the restaurant seems to have doubled its proportions, the kitchen is now a football field away from us, and everything between it and our table has been consumed.” In the two stories that follow, “The Histories” and “Secret Message,” again the rule of three is on display, the pieces split into sections that take up questions of memory and the power of names. And in “Partners,” a beautiful and violent flash fiction, we witness worlds dramatically shifting four times for one couple, but we understand that this is just another day (minute? second? Planck time?) within a shared life together, surviving the fray (jungle rain, sharks, exploding volcano, the suburbs) by loving each other through the bitchiness that emerges in the effort. |

Half of Masterworks is devoted to the novella “Land,” which could deserve the lion’s share of focus based on length alone, but is also the most confounding and compelling story of all—the one that got away. In the beginning, the narrative tone is seemingly open, confessional. There is a formality in the cadence, an immediacy of storytelling that is reminiscent of a first-person Henry James or Edith Wharton work, especially their ghost stories. The story begins directly: “I was supposed to be looking after a friend’s huskies for the week while he was away for work.” The “friend,” we later learn, is also the protagonist’s landlord, and the protagonist loses one of his huskies, either Ares or Decatur—he’s not sure which—straight off. They are meant to be taking care of the huskies at the landlord’s cabin, which “sat alongside a small, pristine lake,” a lake which our narrator immediately deems “a place of significant and potent meaning.”

So, the title “Land” is an interesting choice, as the story’s setting primarily alternates between a leaky bathroom in Harlem and the bottom of a lake in upstate New York. The narrator gives up on the huskies, mostly, and without any particular drama or dark intention, sinks to the bottom of the lake, descending through multiple portals along the way and realizing that they can navigate this new world, though they are unsure whether they are living or dead. There are pages and pages of Gothic, ornate description of the wanderings through this sunken world: I struggled through these sections, but I admit to being impatient with fictional worlds that must be described in great detail; I’m not really a fan of Tolkien, say. I was content to skim these sections, all the while attempting to piece together the concurrent puzzle of what was happening back in Harlem, in flashbacks (I believe) that show the narrator dealing with their anxiety, exacerbated by their confusing relationship to and with the landlord. A pattern emerges, where the narrator is often awoken by the landlord’s insistent texting, dazed as their headphones loop the soundtrack of the game Castlevania or the sound of an ocarina (which Google tells me might have something to do with The Legend of Zelda). The landlord, armed with the keypad’s code, drops in at a moment’s notice, desiring his tenant’s company in the passenger seat of whatever cool car he’s rented that week. The landlord doesn’t call himself a landlord; he is a property manager, and he works for a murky startup called Narthex. The climax of the novella has the landlord’s parents, who moved from Istanbul when the landlord was a child and manage property themselves, bust in on the narrator in the apartment and begin to furiously clean—in the way that one’s own parents might if they were the type—variously scolding about the filth and nagging him about getting married, with a familiarity that at first stuns the narrator but which he quickly accepts. The end of the novella transports us, with no warning, from the lake to a bus and back again. There is a woman on the bus who “looked, in some way, like” the narrator but is instead, as he says, “who [he] should have been.” The bus winds through the hills, the narrator “watching for change” and leaving us with one question: “What possibilities lay within me yet?” Is this a story about disassociation and sleep deprivation á la Fight Club? Is the landlord Tyler Durden? The novella’s epigraph is from Dante’s Divine Comedy, suggesting another interpretation—but, uh, I haven’t studied the poem. (I went to a state school.) And, so, I come to the end of Masterworks feeling a bit like the narrator from “Land,” stranded on the other side of town after being taken for a dizzying tour in the landlord’s fancy ride. I feel, in other words, wooed but uncertain, and a little bit insecure. Will you want to read Masterworks knowing that you might not totally get it? It depends on whether you, like Jeanne Thornton and Miracle Jones, founders of Instar Books, “are intrigued by the possibilities of texts as social destinations, as performance, and also as digital sculptures, or ‘seeds.’” I found Masterworks to be a fascinating, challenging collection of structural experiments, a kind of narrative exploration of chaos theory. And, well, I never can resist a Scorpio.

REVIEWED BY AMANDA KRUPMAN

Amanda Krupman is a writer from Cleveland, OH. She lives in Brooklyn, NY. Her work has appeared or is forthcoming in Flapperhouse, Smokelong Quarterly, The Forge Literary Magazine, BLOOM, The New Engagement, Punk Planet, and others. Amanda received an MFA in fiction from The New School’s graduate writing program and was recently a recipient of a Jerome Foundation Emerging Artist Residency Award. She teaches writing at Pace University and Middlebury College. |